The science of the spirit

Portfolio

Th science of the spirit

Everyday life at Sustainable Settings, a biodynamic ranch in Carbondale, Colorado.

A biodynamic ranch in the Rockies

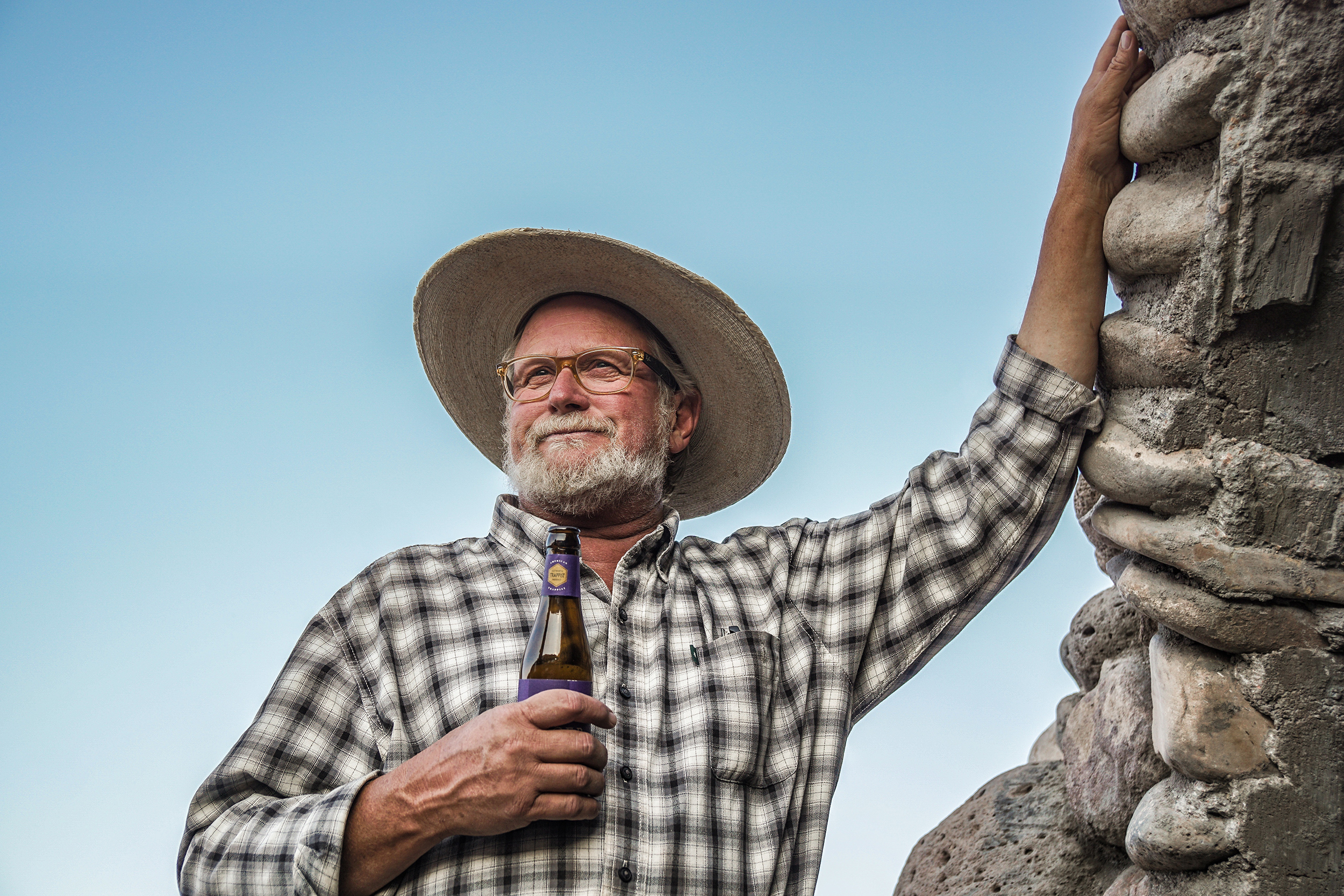

Spanning 97 hectares of Colorado’s rugged landscape, Sustainable Settings is a working model of regenerative agriculture. Pastures support 21 cows, while pigs, chickens, turkeys, geese, and ducks add to the farm’s diversity. Run by Brook, Rose, and their son Shepard, alongside a team of seven, the ranch welcomes 10,000 visitors annually—volunteers, students, and travelers drawn to its ethos of mindful living. Fresh dairy, eggs, pasture-raised meat, and medicinal herbs supply local families, restaurants, and even Whole Foods on occasion.

Beyond food, education is central. Through consulting and workshops, Sustainable Settings is shaping a future where agriculture restores both people and the planet.

The case for generalists in a specialized world

“In highly specialized fields, professionals often fall into the trap of seeing every problem as a version of what they already know,” writes David Epstein in Range. The result? A dangerously narrow field of vision—one that leads experts to hammer away at invisible nails while missing the very structures that hold everything together.

At Sustainable Settings, the approach is different. Here, learning is about breadth, not just depth. Interns leave not as specialists but as generalists, trained to work with soil, animals, wood, and water. They learn to adapt, to problem-solve rather than apply quick fixes, and to collaborate—harnessing collective intelligence rather than isolated expertise.

We live in a world that is complex, fluid, interconnected. The ability to scan the horizon, to make unlikely connections, to imagine beyond the obvious—that’s what will make the difference. That’s what will save us.

Beyond food, education is central. Through consulting and workshops, Sustainable Settings is shaping a future where agriculture restores both people and the planet.

A Ranch, a Vision, a Paradox

Brook and his wife, Rose, are the driving force behind Sustainable Settings, but the name itself carries an irony. Despite its commitment to self-sufficiency, the ranch isn’t financially sustainable—it survives on the generosity of wealthy benefactors.

The reason becomes clear as soon as we discuss costs. Land, buildings, machinery, fences—none of it is feasible to sustain on the sale of milk, meat, and vegetables alone. Sensing my skepticism, Brook gestures toward neighboring estates. “That’s Victoria’s Secret. That’s Pepsi. You know?”

We are in Aspen Valley, where second, third, and fourth homes belong to some of the richest people on earth. Colorado’s breathtaking landscapes, once a refuge for pioneers, have become a playground for the ultra-wealthy. The pandemic only deepened the divide—remote work allowed more affluent buyers to move in, driving up housing costs and leaving local businesses scrambling for workers who can no longer afford to live here.

Sustainable Settings is many things—an experiment, a community, a school for generalists, a vision for more ethical agriculture. It’s also a constant struggle, a ranch trying to give back to the land as much as it takes. Will it ever sustain itself solely on its own production? Brook hesitates. “Maybe,” he says, but the uncertainty in his voice lingers.

Biodynamics: farming in rhythm with the cosmos

A biodynamic farm is more than just a piece of land—it’s a living organism. Everything is connected: soil, plants, animals, insects, cosmic forces, and the people who work the land. The goal is balance, a system where each element supports the others.

Central to this philosophy is the biodynamic calendar, which aligns farming practices with the movements of the moon, planets, and zodiac signs. The idea is simple yet profound: timing matters. Depending on celestial rhythms, certain crops are planted, harvested, or tended to, following patterns that farmers have observed for generations.

But it’s the soil that truly holds the farm’s life force. Biodynamics treats it with homeopathic-like preparations—small but powerful doses designed to nourish, heal, and energize. These mixtures, made from quartz, manure, flowers, and medicinal plants, are enclosed in animal-derived vessels like cow horns or intestines and buried underground. Months later, they are unearthed, transformed, and ready to enrich the land.

Biodynamics is more than an agricultural method—it’s a way of seeing the world. A belief that farming isn’t just about growing food, but about restoring a deeper connection between earth, sky, and spirit.

Ophelia’s Last Gift

Ophelia was harvested here, on the farm, during a biodynamic workshop. Her meat went into the fridge, her guts became part of biodynamic preparations, and the rest of her body returned to the earth.

She wasn’t just any cow. Ophelia was the difficult one—the one who kicked, who made milking a battle, who arrived at the farm at four years old and never quite settled. Maybe that’s why they named her Ophelia.

Her death was marked by ceremony, a ritual of recognition and gratitude. A sharp shot to the skull. I was crouched nearby, camera in hand, tears in my eyes. I pressed the shutter as soon as I heard the crack of the bullet. By the time I lowered the camera, she was already down.

Her body twitched. One eye, open and unmoving. Then the sound of running water—her urine spilling onto the ground, startling in its volume. A final release, as if life were still pushing through her. Her udders leaked a slow trickle of milk. The last drop.

They gathered around her, touching her cooling body, honoring her. Some cupped their hands beneath the wound and drank her blood. Then they lifted her—her strong, heavy body—and carried her away. I watched as they severed her head, a blade working left and right until it came free. Her tongue lolled out, absurdly. For a second, she looked almost playful. I kept crying.

Piece by piece, she was taken apart. The last thing I saw was the skin of her skull, surrounding an eye that was no longer there.

Building Without a Blueprint

A superadobe—a structure patented by an Iranian architect—is made of stacked bags of soil, a simple yet ingenious design originally intended as a root cellar.

But what made this project unforgettable wasn’t just the structure itself. It was the process—the trial and error, the problem-solving, the unexpected discoveries.

Take Daniel, for example. By accident, he found that angling the screwdriver against the wood caused just enough vibration to let the concrete settle perfectly into every gap. Small insights like these shaped the entire build.

They worked from a rough sketch, but without rigid instructions. No one had built a superadobe before. Every day brought a new challenge, a mistake to fix, a solution to invent. And that was what I loved most: the creativity of it all—thinking, testing, adjusting, moving forward. Until the next obstacle appeared.

Recently in Portfolio

elettrapistoni